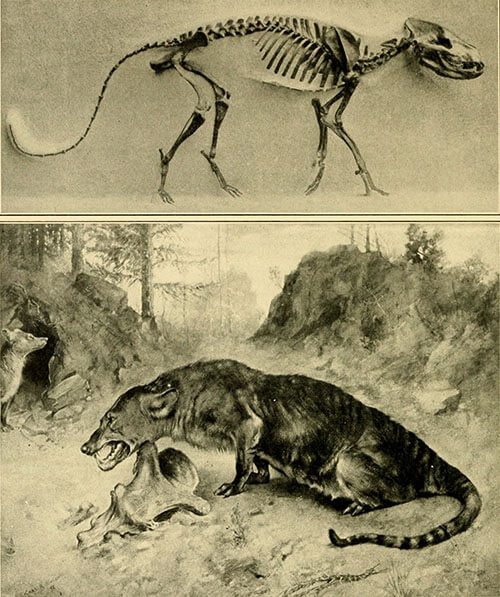

Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History is known to be in the possession of some fascinating exhibits, but the skeleton of a Dromocyon vorax is one of the most recondite fossils in the museum’s collection, of which the experts know very little about so far.

The fossil was found in 1875, not by archaeologists of some kind, but by 2 field workers named Sam Smith and Jacob Heisey, as they dug in the 45-million-year-old Eocene rock of Wyoming’s Bridger Basin.

Since its discovery in 1875, the fossil underwent dozens of osteological examinations, and it has been acknowledged to be the more complete representative of Synoplotherium, named so by Edward Drinker Cope, an American palaeontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist and ichtyologist. His proposal of mammalian molars is the most remarkable among his theoretical contributions.

This mammal fossil of a Dromocyon vorax was especially accounted for its dog-like aspect and its presumed ferocity and appetite, and even today stirs the curiosity of all the visitors, many coming especially for this exhibit.

Roughly the size of a German shepherd, Synoplotherium are also known as mesonychids, or “wolves with hooves”, for their tail longer than of any dog’s, bigger skull and flat feet that ended with blunt toes instead of claws.

An intriguing controversy goes around the specimen’s access towards the general public, from Othniel C. Marsh, a preeminent scientist in palaeontology and known rival of Edward Drinker Cope. Marsh asserted that those bones specifically are a matter for experts only and shall be removed from the public display, in order to make possible further examinations of the fossils.

As expected, there were plenty of people to disagree with Marsh’s decisions, so immediately after his death in 1899, the bones of Synoplotherium were finally a sight for the public, a glimpse into a point in the past when the mammalian evolution took a few crucial turns and Dromocyon vorax was the apex predator of that time but still an oddity, along with the Eocene’s Patriofelis. To this day, these two species remain a partially-understood mystery.

Paramount information regarding the Synoplotherium has been extracted from an extensive review on Eocene mammals made by palaeontologist Jacob Wortman in 1902. His elaborated conclusions were based on observations of Dromocyon vorax’s over-sized skull and what was left of its tail. During his analysis he came across some unexpected traits:

“The lower jaw of the individual under consideration is of unusual pathological interest, as showing, among these ancient animals, the result of healing of a fracture,” Wortman wrote. “This Synoplotherium not only had the left side of its jaw cracked right at the midpoint, but survived the ordeal to old age, as shown by its worn-down teeth.”

Palaeosyops was about the size of large cattle

Though it is uncertain what broke the carnivore’s jaw, palaeontologist G.R. Weiland presumed to be the mark of a rhino-like Palaeosyops encounter, during a raid on their young. There is so little known about the Synoplotherium that besides a dental formulae and a high running speed, nothing else is revealed in the “Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America and The Beginning of the Age of Mammals”.

Is there a viable reason on why experts have neglected any further research? Any small creature that has lived throughout the prehistory, every living being had its place in the animal kingdom, influencing the way other species have evolved, leading to the fauna we see today slowly being driven to extinction. The only way to help other species from extinction is to have a deeper understanding of the history of as many ancient extinct species and the exact circumstances when their life-cycle ended. If we don’t learn from fossils, we risk becoming fossils ourselves.

(Source)