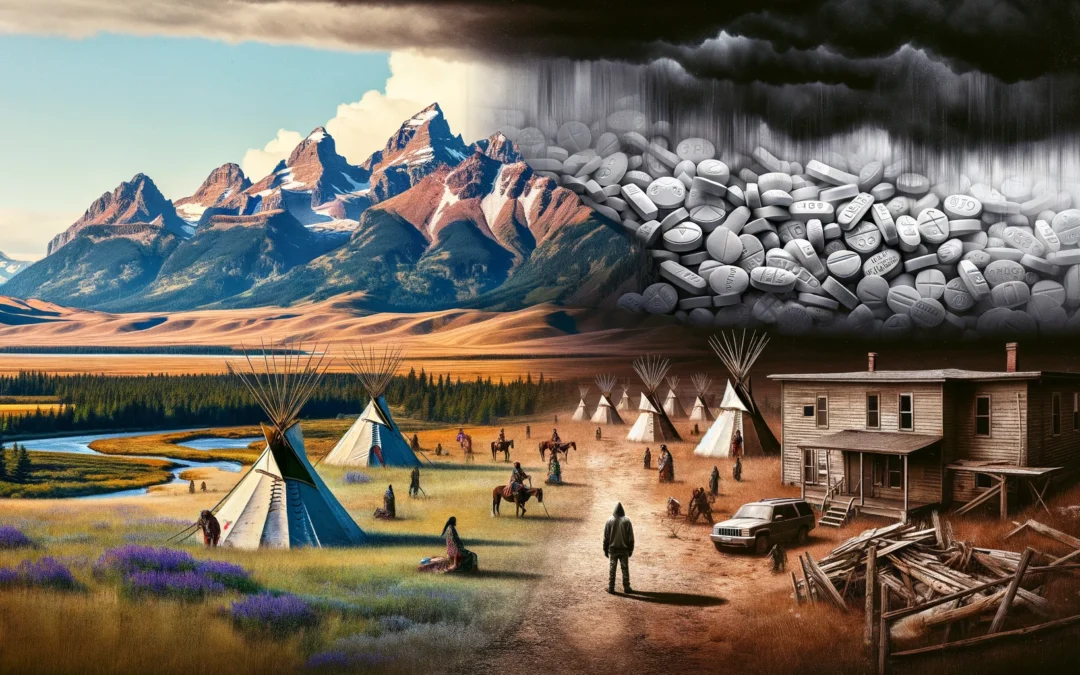

The Blackfeet Reservation in Northern Montana is a landscape of vast beauty, yet it is currently facing a severe crisis due to an influx of fentanyl. “It’s as if fentanyl is raining on our reservation that I’ll do anything to help,” states Marvin Weatherwax Jr., a tribal leader, highlighting the dire situation. The reservation’s struggle with drug activity is largely attributed to Mexican cartels, which target community members for sales and use their homes, often situated in remote areas, as distribution centers. “They’ve infiltrated our reservation, they’ve married in, they’ve basically set up shop. It’s just a problem that won’t go away,” Weatherwax Jr. explains.

The transformation of the reservation at night is stark, with a “whole different population” taking over, according to Weatherwax Jr. This change underscores the pervasive influence of one of Mexico’s most dangerous cartels, the Sinaloa, formerly led by the infamous Chapo and now partly by his sons. This cartel specifically targets the Blackfeet and Montana’s six other reservations, flooding them with a steady supply of drugs, including fentanyl.

“Why Montana?”

A rare insight into this illicit trade was provided when a Sinaloa cartel member was stopped by police on one of the reservations during his journey from Mexico. This incident led to the conviction of three cartel members for drug and cash smuggling into Montana, marking one of the state’s largest drug busts. Over 700,000 fentanyl pills were seized, with the U.S. Attorney for Montana, Jesse Laslovich, overseeing the federal prosecution. “Why Montana? Fundamentally, it’s money. It’s big business. These are transnational criminal organizations; they’re sophisticated, have a lot of resources, and are as dangerous as they come,” Laslovich stated.

The cartels exploit the high price of fentanyl on reservations and the sparse law enforcement presence, creating fertile ground for their operations. Stacy Zin, who until recently ran the DEA in Montana, emphasized the unique vulnerability of the state. “Drugs in other cities are saturated; you have multiple cartels. Up here in Montana, it’s pretty much wide-open space and territory for them to grab. Profit margins soar the further away from the Mexican border you go,” she explained. A fentanyl pill, costing mere cents to produce in Mexico, can sell for up to $100 on some Montana reservations.

The Law Enforcement Crisis

The lack of law enforcement exacerbates the problem, with fewer than 20 DEA agents covering the entire state. The reservations are particularly underprotected, with very few Tribal Police officers to cover vast areas. This situation is vividly illustrated on the Northern Cheyenne reservation, where boarded-up meth houses signal a profound drug crisis. Despite a lawsuit against the Bureau of Indian Affairs for more support, the number of police officers has dwindled, leaving the community even more vulnerable.

Federal officials acknowledge the need for more action. “We always can do more and need to do more,” one official admitted, highlighting the challenges of maintaining law and order in such expansive and underpoliced regions. Tribal leaders are witnessing devastating effects, including spikes in crimes such as sexual abuse, human trafficking, and domestic violence, all exacerbated by the drug crisis.

The Blackfeet community declared a state of emergency two years ago after a tragic week saw 17 overdoses and four deaths. “The drug problem on our reservation is so serious that it’s pretty much wiping out a generation,” Weatherwax Jr. lamented. The call for more resources is urgent, with Zin emphasizing, “We are fighting this problem standing on one leg and half the time we’re handcuffed.” The battle against the cartels is tough, and as it stands, they are winning.

A Former DEA Agent’s Take

Stacy Zinn began her tenure with the Drug Enforcement Administration in El Paso, Texas, focusing on the investigation of Mexican cartels. Her career then took her to Afghanistan and Peru, where she pursued narcoterrorists and cocaine traffickers. In 2014, Zinn was reassigned to Montana, eventually leading the DEA’s operations in Billings, Great Falls, and Missoula.

“When I was promoted and they said, ‘You’re going to Montana,’ I’m like, ‘Montana? Are there drugs in Montana?’” Zinn shared, reflecting on her initial reaction to the transfer. She retired in October after a 23-year career with the DEA.

Montana, often celebrated as “the last best place” in America, is home to 1.2 million residents scattered across its 150,000 square miles of mountainous and rugged landscapes.

The state’s battle with drugs initially centered around locally produced methamphetamine. However, by the mid-2000s, crackdowns on the chemicals needed to make meth led to a decline in local production. This void was quickly filled by Mexican cartels, which introduced a highly potent form of meth into the U.S., targeting particularly the indigenous communities. Zinn was taken aback by the extent of the meth issue upon her arrival in Montana a decade ago, only to be further challenged by the emergence of fentanyl, a substance cheaper to produce and significantly more lethal.

In more established drug markets like Seattle and Denver, a counterfeit fentanyl pill produced for under 25 cents in Mexico can sell for $3 to $5, but in Montana’s remote areas, the price can soar to $100. Zinn noted that Montana was one of the last states to attract the attention of Mexican cartels, but that quickly changed due to the lucrative profits.

“The profits are just out of this world,” Zinn remarked, finding herself over 1,300 miles from the southern U.S. border yet again confronting the operations of Mexican cartels, including the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation cartel, or CJNG.

“I got excited,” Zinn admitted. “This is the territory I know and understand.”

Initially, Zinn only caught faint signs of cartel activity. However, over time, she observed that cartel associates became increasingly bold, frequently appearing as they aimed to widen their footprint. “The cartel will send out their advance team or individuals to get to know who’s distributing small amounts on this reservation, who can we get our claws into,” Zinn explained. “And then when they do that, then they own them. We’ve seen that over and over.”

Cartel members often target women, leveraging their homes as operational bases.

“They know who to choose,” stated Stephanie Iron Shooter, the American Indian health director for the Montana Department of Health and Human Services. “Just like any other prey predator situation — that’s how it is.”

The impact of the drug crisis has been particularly severe on Montana’s Indian reservations.

From 2017 to 2020, the opioid overdose death rate in Montana nearly tripled, increasing from 2.7 deaths per 100,000 residents to 7.3. Furthermore, in the decade up to 2020, the overdose death rate among Native Americans in Montana was over twice that of white residents, as reported by the state Department of Health and Human Services.