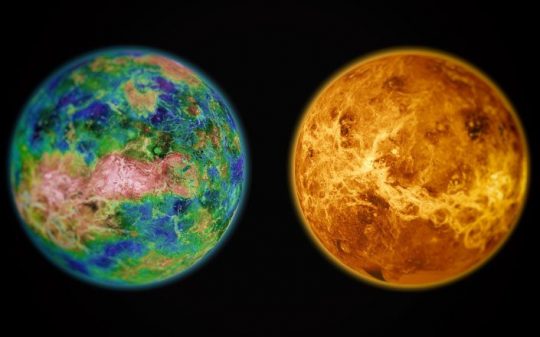

Once a paradise, now a toxic inferno. That’s the way the first habitable planet in the Solar System crumbled.

For some time now, astronomers have been aware of the many similarities between Earth and Venus. The second and third planet from the sun were born roughly in the same area and out of similar accretion material. Their comparable radius and density attest their common origin.

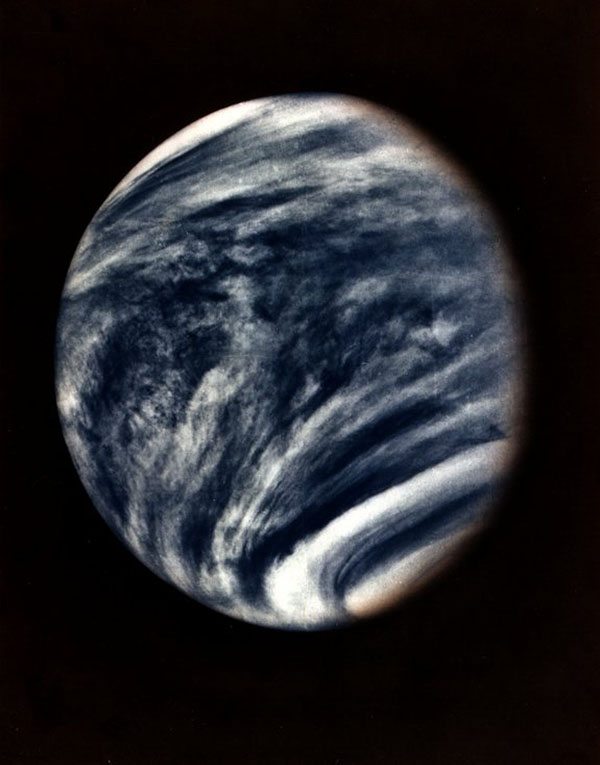

But while Earth sits cozy in the habitable zone and still harbors life, Venus turned sour a long time ago. Nowadays, the surface temperatures on the planet reach lead-melting values while the noxious CO2 atmosphere laced with sulfuric acid pushes down 90 times harder than Earth’s. Furious winds violently push its atmosphere, which encircles the planet in just 4 days. This is a curious phenomenon, since the planet itself completes a full rotation around its axis in 243 Earth days. And since it revolves around the sun in less than that (225 days), Venus is the only planet where the day is longer than the year.

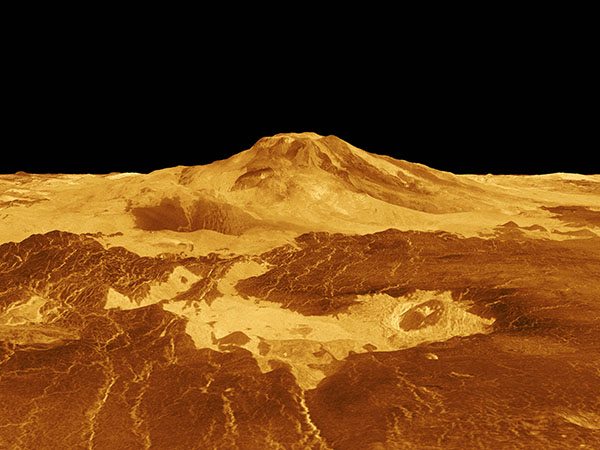

The planet’s surface is so inhospitable it kills any probes we send in a matter of hours. The current record-holder is the Soviet-built Venera 13, whose surface lander touched ground in 1982 and was able to transmit data for a full 127 minutes before its demise. In comparison, the Curiosity Rover just celebrated its fourth (Earthly) year on Mars.

The primary reason for Venus developing into such a hellish landscape is its proximity to the sun. While Earth orbits our star in the Goldilocks Zone, Venus sits one row (25 million miles) closer and receives twice as much sunlight. Coupled with its slow rotation, the planet’s thick blanket of clouds sustains a greenhouse effect the likes of which we hope never to see back home.

Venus’ current unfriendliness to life is obvious but that doesn’t mean the planet was always this way. Various clues have long provoked astronomers into thinking the planet might have been significantly cooler in its past, allowing liquid water to exist on its surface and even form voluminous oceans. Modern models suggest this period could have lasted long enough for life to appear, evolve and flourish.

A recent study issued in the scientific publication Geophysical Research Letters suggests Venus conditions were favorable to life for billions of years. Led by NASA’s Michael Way, a team of scientists at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies managed to perfect the first three-dimensional climate model detailing how early Venusian conditions looked like. The same type of computer simulation is used to predict how human activity might impact future Earth’s climate conditions.

This latest study represents a vast improvement because it factors in a multitude of circumstances that previous attempts couldn’t. In the words of University of Idaho astronomer Jason Barnes, there is a “real difference between a back-of-the-envelope calculation and actually plugging it into a more sophisticated model.”

In order to assess the potential life-favorable conditions that existed on Venus nearly 3 billion years ago, the team had to improvise and fill in the blanks with some assumptions. Based on relevant data, the astronomers presumed that Venus once had liquid water on its surface; they conservatively estimated it formed a shallow ocean only 10% the volume of the global ocean on Earth. The results were staggering: 2.9 billion years ago, surface temperatures on Venus reached a mild 52 degrees Fahrenheit (11° Celsius). This is due to the fact that back then, the Sun was younger and had a lower energy output.

Early Venus probably looked a lot like Earth.

The team then ran another simulation for 715 million years ago. Terrestrial geological data shows that during that period, Earth was traversing a deep freeze that would last for 120 million years. Surface temperatures on the equator of Snowball Earth were comparable to those of modern-day Antarctica. Most of the microscopic fauna was wiped out, with the only survivors eking out a living in isolated pockets of open water.

During the same time period, Venus sported a mild 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15° Celsius). If the temperature increased by only 7° F over the course of 2.185 billion years, astronomers reason liquid oceans were present during the entire period. Having oceans of life-sustaining water for billions of years means Venus could have been a paradise, even at a time when Earth was far from being hospitable. Oh, how the wheels were turned!

“To me the real takeaway message is that Venus could have been habitable for a significant period of time, and time is one of the key ingredients to being able to originate life on a planet,” said Lori Glaze, astronomer at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

The team believes clouds were responsible for keeping Venus wet for so long. Models show they formed on the side of the planet that was exposed to sunlight, acting as a bright shield that deflected the sun’s rays. The other side remained cool and allowed heat to dissipate into space.

This recent study means a great deal for mankind and will influence the way we search for exoplanets that might harbor life. Prior to gaining this understanding of planetary habitability mechanisms, astronomers excluded planets that were orbiting close to their stars from the list of potential candidates for life. “The community should be careful about ignoring worlds that are very close to their stars, like Venus-type worlds,” Michael Way says. The good thing is that planets near the inner edge of the habitable zone are easier to study than those farther away from their stars.

Hubble’s replacement, the James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in October 2018, will specifically look for exoplanets orbiting their suns at close range. It would seem we’re in for some major discoveries in the near future.